...Among the real philosophers and career academics, things are worse. In 1989, Brian Leiter, now an analytic philosopher and law professor at the University of Texas at Austin, declared open war on continental philosophy by launching the Philosophical Gourmet Report. In the PGR, Leiter offered a ranking of the top philosophy programs in the US. At first hard copies of the rankings were distributed; then in 1996 the PGR went online. Geared toward prospective undergrads and based on the “quality of faculty” factor, the rankings were clearly, profoundly biased toward analytic programs. Some continental-leaning departments hung near the bottom of the list; most didn’t make it at all.

On the PGR website, which is now very fancy, there’s a section called “Continental vs. Analytic Philosophy,” a concise version of the introduction Leiter wrote for the book A Future for Philosophy. Here he distinguishes between them as two styles of doing philosophy, rather than categories for the kind of books to be read:Continental philosophy is distinguished by its style (more literary, less analytical, sometimes just obscure), its concerns (more interested in actual political and cultural issues and, loosely speaking, the human situation and its “meaning”), and some of its substantive commitments (more self-conscious about the relation of philosophy to its historical situation).

Leiter seems to think he’s dropping a bomb—note the disparagements of “obscure” and “loosely speaking”—but the house of philosophy had begun to self-destruct half a century before. Since the 1950s analytic philosophers have made the same complaints: that continental philosophy has a messy literary quality, that it wastes time with “concepts-in-quotations,” and that it bothers itself with cultural things like genocide and the Internet. And yet, boom! Like a frantic seven-year-old, Leiter defends his kind of philosophy by pushing out people who don’t agree with him.

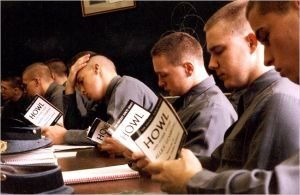

Not all continental scholars are concerned with historicity. Some are: the postmodernists, the feminists, the critical race theorists. But what the continental has tried to preserve (and what the analytic has tried to run from) is a sense that, even while pursuing self-preservation, philosophers should never give up on answering questions that are important and interesting to everyone. The analytic philosopher takes his scalpel to the concept of democracy; the continental presents us with an account of the brutal pacification of the east. One is not more philosophically interesting than the other, but certainly the second is more interesting to real people. And after all, there are still real people asking questions—for instance, the undergraduate who takes a course on ancient Greek philosophy and wonders why the platonic philosopher-king banished poetry while on television presidents use the highly poetic rhetoric of wartime. In universities with hard-core analytic cliques, like NYU or Princeton, continental philosophers end up outside of the philosophy department and find a home in comp lit, women’s, or African-American studies. In those settings they won’t be the ones to teach classes on the western philosophical tradition, and the task of teaching the ancients (and the recents) is left to the analytic philosophers. In their classrooms, “meaningful” words are more important than rhetoric, “sophomoric” everyday questions are banned, and in place of natural curiosity a student learns pragmatic methodology.

Continental philosophy isn’t obsolete. But the continental education, that ideal classroom in which Wittgenstein and Foucault are both taught, is becoming very difficult to find. This should worry us more than the fates of individual graduate students, whichever gang they choose. Today’s missiles are being dropped east of the Holland House Library.

Food for thought, as one revisits such things in turning to America.

Update: It has come to my attention that this polemic, excerpted above in the general interests of Internet communism, may be, as indeed polemics often are, slightly unfair, in this case to Brian Leiter, and furthermore that it may even contain factual inaccuracies of one degree or another. Please feel free to read his partly tangential, partly confirming, in any case blustering reply (linked several times by one "anonymous" soul in comments below) and come to your own well-nuanced and adult conclusions as always, needless to say.

Update 2: Also, dear fellow "random morons" if you will: please do take a look at this, and this. Thanks.